Aemilia Melissa: Genre Matters

- Skye Shirley

- May 21, 2021

- 4 min read

Salvete! Hello! Thanks for taking the time to explore some women's Latin with me today.

One goal in this project is to make sure that I show how deeply (if unfortunately) relevant the issues relating to 17th century women Latinists are to our own lives. Today's poem provides us with a perfect example of this.

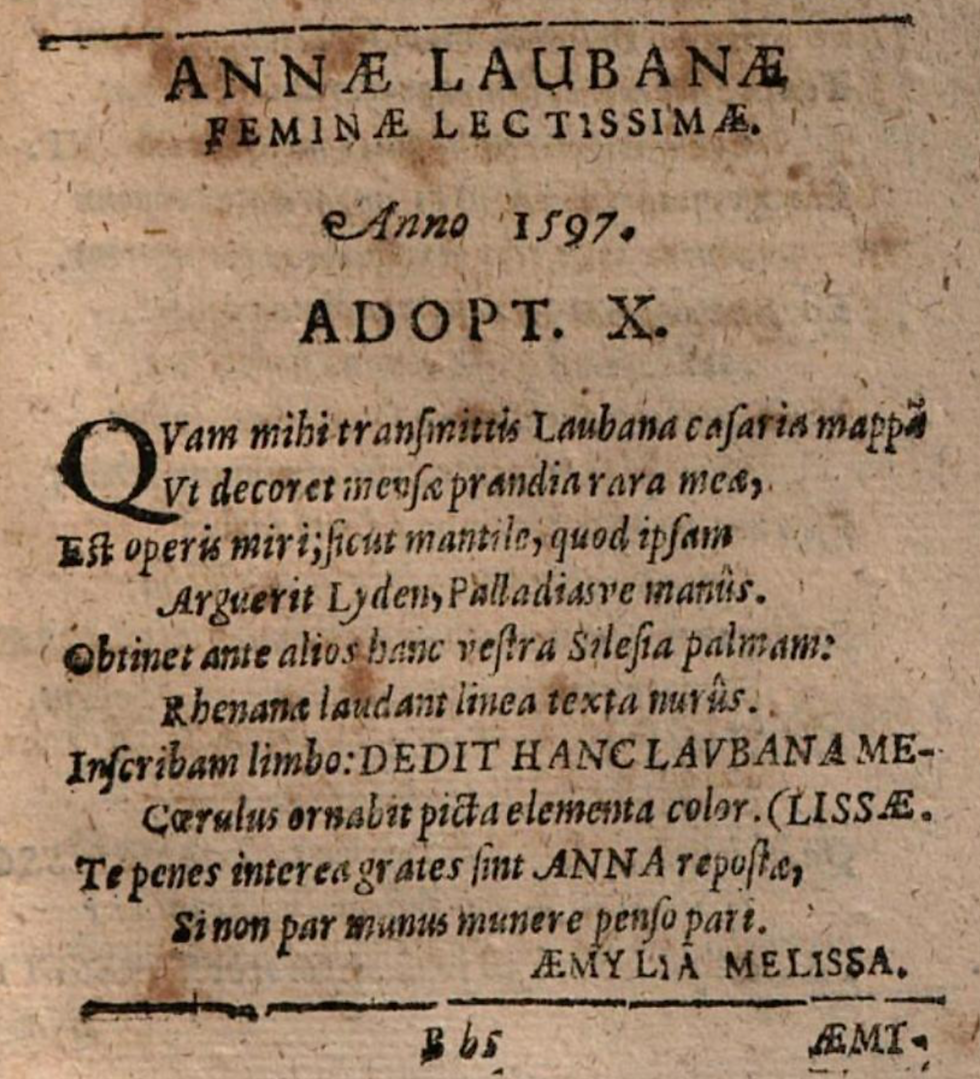

This morning I had the incredible opportunity to find a Latin poem at the British Library by Anne Lauban. She lived in Szprotawa (then Silesia, now Poland) from 1574-1626 and seems to have had a friendship with Aemilia Melissa, the wife of the famous Paul Melissus who corresponded with Queen Elizabeth I. That poem led me to the book it was originally found in, "M. Laubani Musa Lyrica" (377). There, just above an expanded version of Lauban's poem, was the following poem from Aemilia Melissa herself:

Annae Laubanae

Quam mihi transmittis Laubana casaria mappā

Ut decoret mensae prandia rara meae,

Est operis miri; sicut mantile, quod ipsam

Arguerit Lyden, Palladiasve manus.

Obtinet ante alios hanc vestra Silesia palmam:

Rhenanae laudant linea texta nurūs.

Inscribam limbo: "Dedit hanc Laubana Melissae"

Coerulus* ornabit picta elementa color.

Te penes interea grates sint Anna repostae,

Si non par munus munere penso pari.

-Aemylia Melissa

*Coerulus = caeruleus/blue

This is an epistolary poem, which is a letter in verse, thanking her friend Anne for the gift of a cloth napkin or handkerchief. What's extraordinary about this is her words: "Inscribam limbo" ("I'll write in the margin"). In some ways, those two words encapsulate so much of women's writing: it is in the margins, of our curriculum, of our culture, and even of many women writer's lives, between naptime and dinnertime, researching and grading. Where is the time, the space, to squeeze it in? Why isn't the same asked of men's writing, and of men?

When she says "I'll write in the margins," Aemilia promises her friend that she'll personalize this special gift even more by embroidering the Latin words saying, "Laubana gave this to Melissa," and that she'll decorate it with blue patterns. This touching gift just became even more meaningful because the recipient chooses to repay the giver in embellishments and this Latin poem. She says it ought to be equal to the gift she received.

Poems like this make me wonder-- where are all the texts we have lost? Some probably grew moldy, moth-eaten, or were fed to fires long ago. Others may be in private collections or undigitized archives. But I think with women's Latin, we need to look in unexpected places. We need to expand our search to explore outside of genres used by men, even away from paper. Could a napkin carry a Latin message by a woman? What about a portrait, like the one to the left by Catherine van Hemessen? The words in the upper right say "Ego me pinxi" ("I've painted myself") and are as authoritative as the artist's own steady gaze.

Genre has always been a feminist issue, as genre is one way of keeping women in the margins, in "limbo." Few women had access to schools of philosophy and scientific circles, so our language does not always look the same as men's language. Our philosophy might be captured in a nursery rhyme we sing. Our Latin might be captured on a cloth napkin. Or our scientific experiments might resemble those of 17th century nun Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz, who "even when ordered to put her books aside, found herself studying natural phenomena in the kitchen or by observing children at play" (A Woman of Genius, p. 177). Policing genre is one way of policing women, and questioning the very boundaries of genre is one step toward balancing the canon.

This issue isn't one just for Latin bookworms like myself. Take this modern example: I recently found out that Jessica Simpson wanted to have a career in Christian music. She came from a Christian family and took part in her mother's exercise program called "Jump for Jesus." She originally got into singing as a pre-teen to overcome a car accident that left her with a stutter, and through music she found her voice. She wanted to sing the songs she had been raised with— Christian songs— and to become a Christian singer. Her new career took her to numerous churches at first, but she was forced to give that up because of the feedback that her breasts were too big for the genre. Notice how even this article (from 2009!) puts the blame on her breasts, which "caused" the men to "lust." It's a strange inversion of female pop singers being told their breasts are too small! What do we miss when we fall into the trap of genre? A napkin of Latinate female attachment? The beautiful voice of a pre-teen girl connecting to her faith?

When you next go to a bookstore or library, ask yourself where women fit within genres. Are men's biographies being categorized as "philosophy" or "politics" whereas women's are resigned to "memoir?" What of writers like Audre Lorde and bell hooks, who are black lesbian scholars and who risk being placed in Women or Sexuality or Race, when there should be no "or" at all? In what way does genre keep some voices out and amplify others?

For those who might think Latin isn't relevant to today's teens, maybe it's not that it's not relevant, but that we aren't looking in the right places— for who's to say this humble poem about embroidering a napkin promotes less discussion, less introspection, and less academic rigor than an excerpt from Caesar's Gallic Wars?

Comments